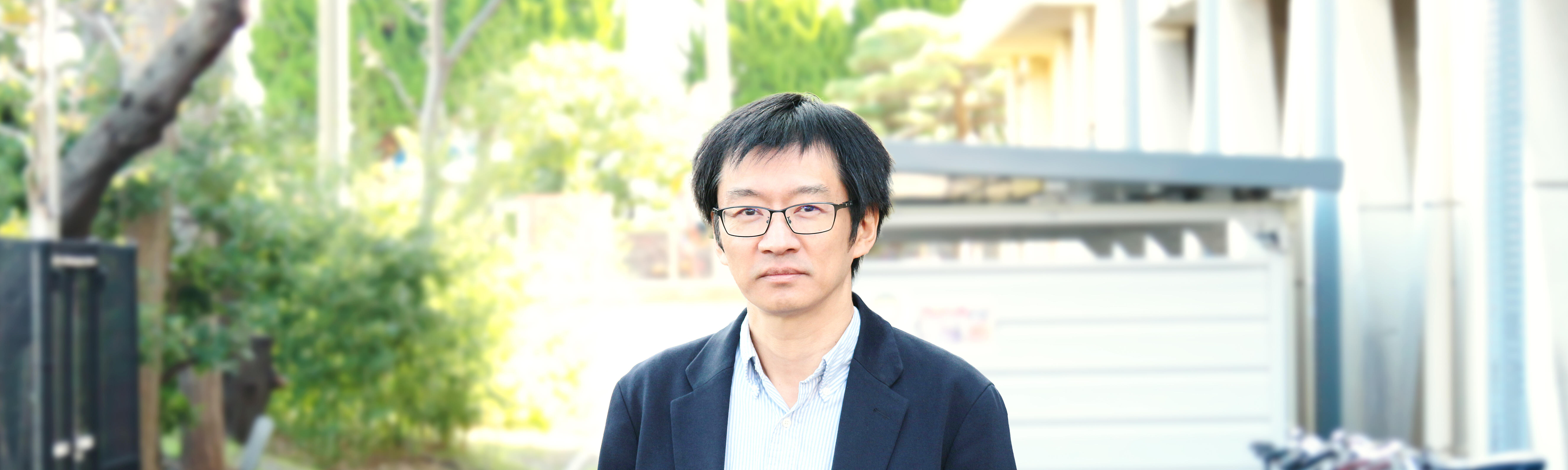

Hideaki Matsui

Professor, Dept of Neuroscience of Disease -Matsui Lab

Interview

Could you share details about your career so far and your current research focus?

Since childhood, I have aspired to be a researcher, inspired by reading biographies of notable figures. I was particularly impressed by Einstein's brilliance and the groundbreaking discovery of penicillin by Fleming. I'm also a fan of "JIN", a historical and medical TV drama adapted from the manga of the same title. When choosing my career path, I struggled to decide between science and medicine but ultimately enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine at Kyoto University. However, university classes didn't particularly capture my interest. Instead, I immersed myself in extracurricular activities, such as participating in the medical school table tennis club and working part-time as a math tutor. This lack of focus on academics led to my failing the neuroscience exam seven times, but ironically, it was this challenge that ignited my fascination with neurology. Initially, I considered joining a laboratory focused on basic research. However, influenced in part by the NHK TV documentary program "THE UNIVERSE WITHIN III: Gene DNA", I ultimately decided to pursue a path in the Department of Neurology at Kyoto University.

I spent a year working at Kyoto University Hospital and four years at Sumitomo Hospital, where my interactions with patients deepened my interest in neurological intractable diseases, particularly Parkinson's disease. In my final year at Sumitomo Hospital, I was encouraged by Dr Masakuni Kameyama, then Director Emeritus, and Dr Fukashi Udaka, then Head of the Neurology Department, to attend the Niigata Summer Seminar for Neuroscience at BRI to further enhance my knowledge.

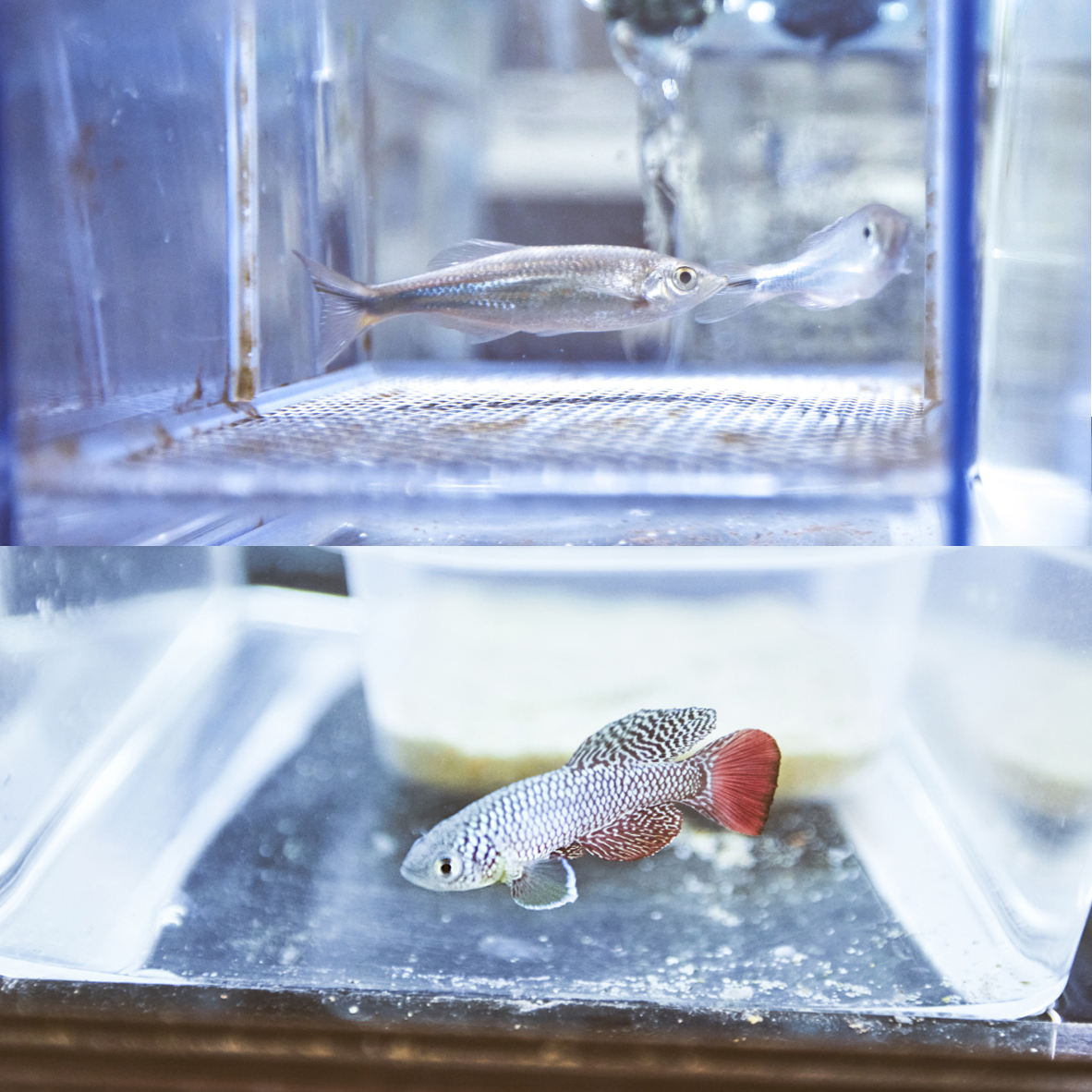

Around that time, Dr Ryosuke Takahashi, who had recently been appointed as a professor in the Department of Neurology at Kyoto University, asked about my aspirations for graduate school and research focus. I responded with a detailed message expressing my interest in modeling Parkinson's disease using alternative organisms to explore its pathophysiology, addressing the limitations of traditional mouse and Drosophila models. By chance, Dr Takahashi was scheduled to lecture at the BRI summer seminar, where I had the opportunity to discuss my ideas with him in person. This interaction led to my joining his lab for my graduate studies. At that time, the Department of Radiation Genetics at Kyoto University was developing a medaka mutant library, and I chose to study Parkinson's disease pathogenesis using medaka fish. This area of research was largely uncharted, and I was thrilled by the challenge, even though it required developing experimental systems from scratch. Through persistent effort, I established several models and published papers. These accomplishments solidified my commitment to a research career. While I initially submitted my resignation to pursue this path, Dr Takahashi declined to accept it and instead supported my decision, encouraging my path as a researcher. Since then, he has continued to provide exceptional support, including glowing reference letters whenever opportunities arise.

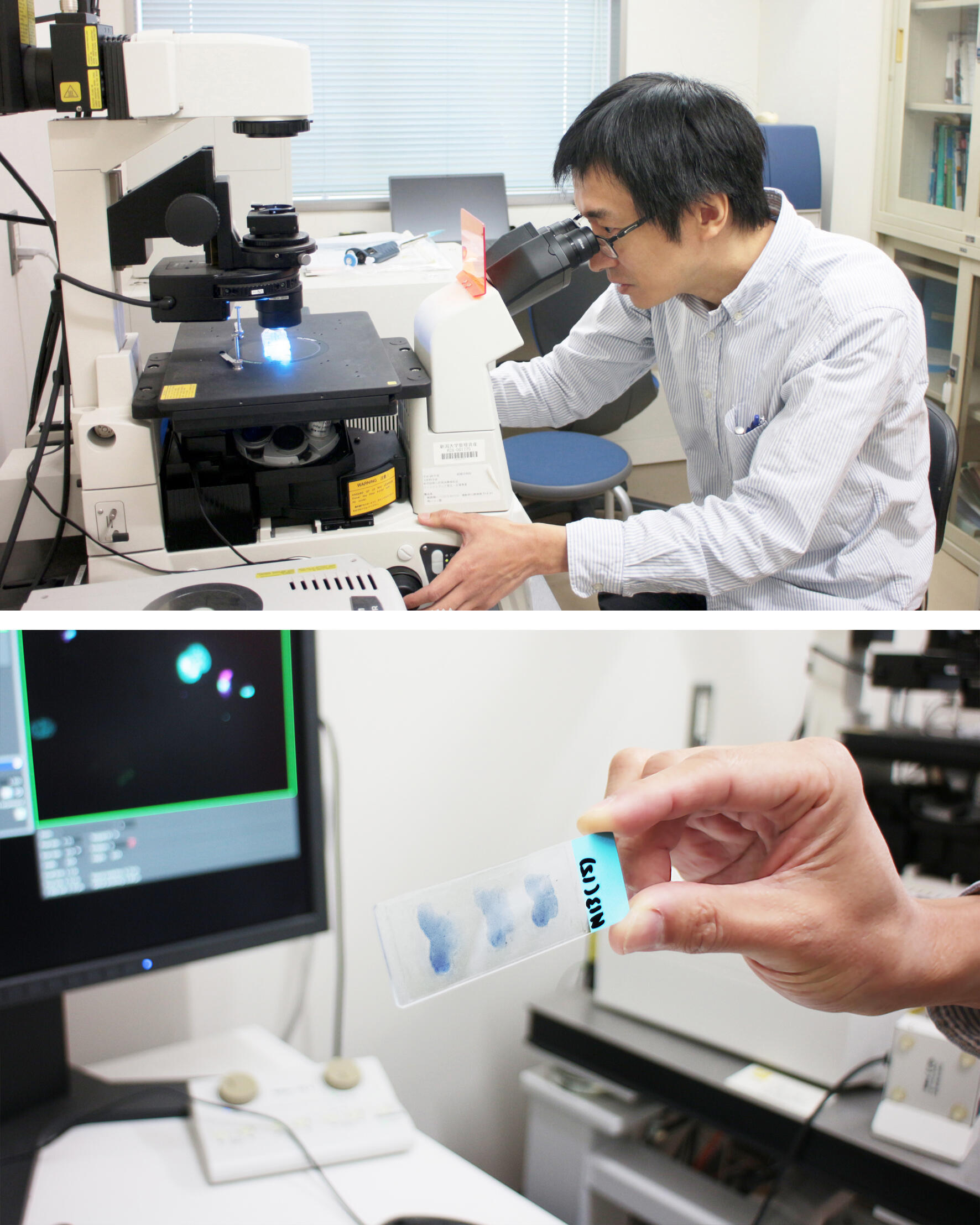

With a scholarship from the Humboldt Foundation, I conducted postdoctoral research in Prof Reinhard Köster's lab at TU Braunschweig, Germany. Under Prof Köster's guidance, I honed my skills in logical experimental design and zebrafish imaging techniques. Together, we developed a functional map of the zebrafish cerebellum, which was later published as a key research paper closely aligned with our original plan. My time in Germany was invaluable, as I actively sought to learn from Prof Köster's logical approach to research. We maintain a good relationship to this day - he sends me birthday emails.

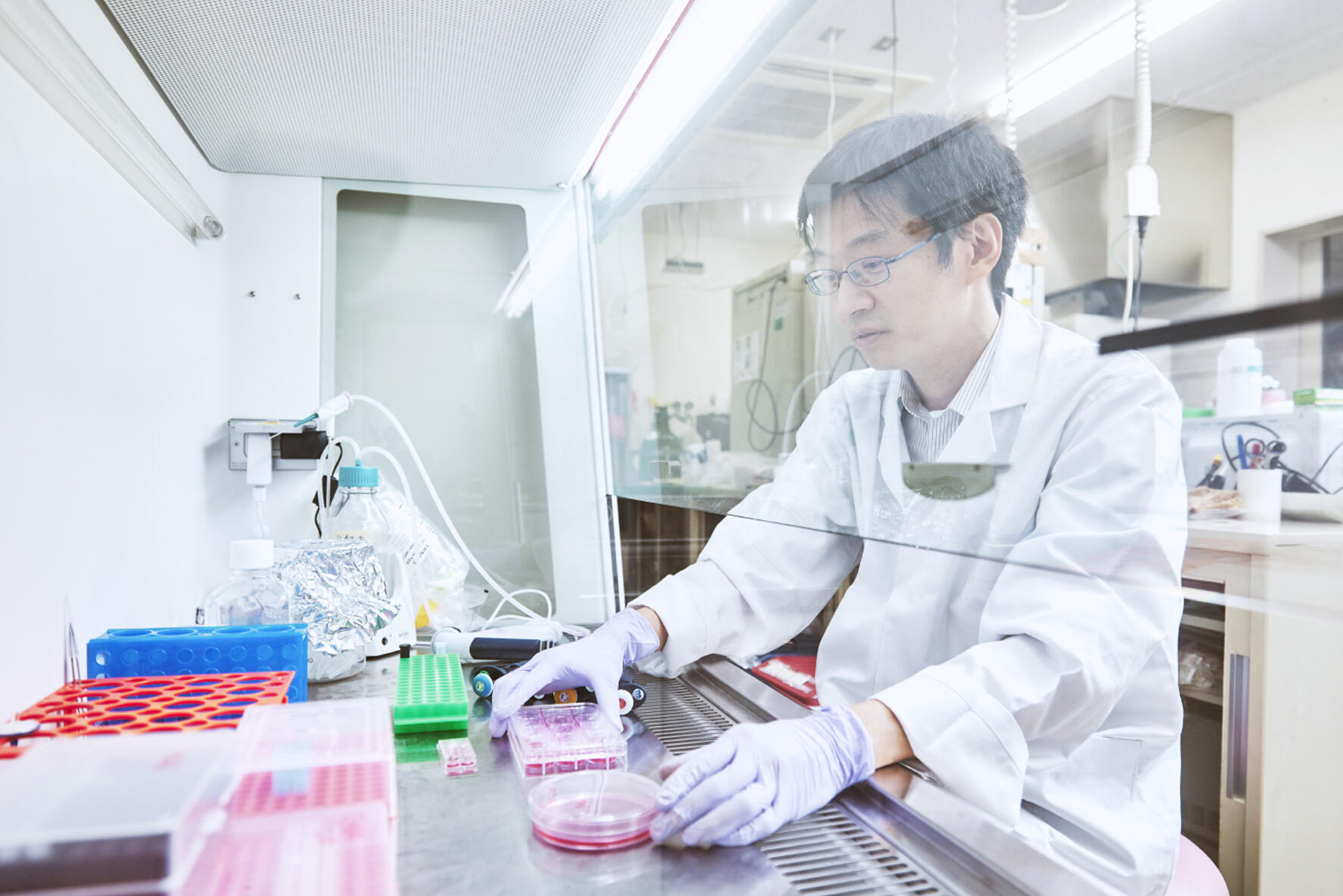

Subsequently, I received a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) and a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research at the University of Miyazaki, allowing me to advance my work. Determined to lead my own lab, I applied for and was accepted into a tenure-track associate professor position at BRI. My research initially centered on medaka, zebrafish, and African killifish--a small fish model for aging. At BRI, I have been able to expand my work to include cultured cells and human autopsy brain samples. Additionally, I now use mice and other species, adapting models and experimental techniques to suit the objectives of my research.

Today, as a professor leading my own lab with a growing team of staff and students, I am dedicated to advancing the fundamental understanding of brain diseases. Our lab's mission, as outlined on our website, encompasses three key goals: overcoming intractable diseases, supporting individuals with disabilities, and leaving a mark in the history of science. We focus on uncovering the mechanisms underlying intractable neurological diseases, including Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple system atrophy, and aging itself. Our research employs diverse animal models, primarily cellular, small fish, and mouse systems, alongside the Brain Bank, a cornerstone resource of BRI, and integrates evolutionary perspectives. By pursuing innovative research methods that even artificial intelligence, 20 to 50 years from now, may not replicate, we aim to explore the evolutionary origins of brain diseases and the functions of disease-causing molecules. Our goal is to contribute to the development of more fundamental and effective therapies.

What inspired you to pursue brain research, and what influenced your decision to join BRI?

The undergraduate exams given by the neurology faculty were particularly challenging, and simply reviewing past exam questions wasn't enough for me to pass. This pushed me to study diligently, and unexpectedly, I became captivated by the complexities of neurology. My interest deepened further through the influence of the NHK TV documentary program "THE UNIVERSE WITHIN III: Gene DNA" and the patients I encountered at the hospital, inspiring me to pursue research on intractable neurological diseases. As someone from Osaka, I'm not particularly fond of snow or cold weather. However, I was deeply impressed by the BRI summer seminar, and after much consideration, I convinced myself and my family that Niigata would be my northernmost boundary, ultimately deciding to apply for the position. While the decision regarding my appointment rested with the referees, but I believe my passion for research closely aligned with BRI's vision and goals.

What advantages do you see in doing research at BRI, and what aspects of its research environment do you find most attractive?

The benefits of working at BRI are difficult to compare without experiencing similar roles at other research institutions for an equivalent duration. However, I feel that Niigata University, as a whole, has a strong concentration of neurological researchers, and BRI, in particular, offers unique advantages. Its focus on neurological diseases and disabilities creates an excellent environment for acquiring knowledge and fostering collaborative research. In my case, much of my work revolves around small fish models, which can sometimes be challenging to justify to reviewers and the public on their own. In this regard, the opportunity to validate findings using human autopsy brains is a significant advantage. Additionally, the institute's size is ideal--not too large nor too small--facilitating collaboration with researchers who are both cooperative and approachable. That said, like anything, it may have its downsides, though.

What aspects of brain research do you find both fascinating and challenging? What obstacles do you encounter?

I believe that exploring the unknown is exciting, not only in brain research but in any field. Recently, BRI welcomed researchers specializing in evolutionary brain pathology, bringing an evolutionary perspective to our studies. Their discussions on evolution, not limited to the brain, are incredibly fascinating. Similarly, research on organisms like jellyfish and slime molds, occasionally seen in other labs, is also highly captivating. Personally, I've been studying neurological intractable diseases for various reasons, and I've come to realize that every field, whether pediatrics or basic science, is both challenging and rewarding in its own way. What truly matters is making the most of your skills, knowledge, and resources in your current environment.

The real challenge in brain research isn't the complexity of the brain itself but the high societal expectations surrounding conditions like dementia, neurodegenerative diseases, and aging. The growing pressure to secure research funding only adds to this difficulty. I often feel weighed down by the looming "milestones" as if carrying a massive rock that I wish I could hurl from Miyazaki to Nagano. Furthermore, researchers have only one way to leave a lasting impact: publishing their work. However, conveying the significance of this to my lab members--something that seems so evident to me--is not always easy.

Do you have a personal motto or guiding principle that you follow in your work?

When pursuing a job, it's important to consider whether you enjoy it and genuinely want to do it. At the same time, I believe it's even more crucial to assess if the job is truly right fit for you. Since my time as a graduate student, I've carried with me the essence of two phrases that, while not exactly mottos, have deeply influenced me: 'Kendo Chorai'* and 'Gashin Shotan'**.

*Kendo Chorai reflects the resilience to overcome setbacks and challenges, using the lessons learned to rise again with renewed strength.

**Gashin Shotan represents the determination to endure hardships and make relentless efforts to achieve a goal.

How do you usually spend your time after research and on your days off? Please share how you refresh and recharge.

On holidays, I often spend time with my family supporting Albirex Niigata and Albirex Niigata Ladies soccer team. I also enjoy exercising with my kids at the park or on Mt. Gomado. However, at the time of this interview, it's been hard to feel refreshed, as Albirex Niigata is currently battling to stay in the J1 League.

What are your goals for the future? Are there any new skills or challenges you'd like to pursue?

I aspire to nurture and develop a team of highly skilled lab staff and students while continually creating original ideas that are uniquely my own.

Please share a message for those interested in pursuing research or graduate programs at BRI.

There's no need to worry too much about the future of your career as a researcher. In many cases, things tend to work out. However, it's challenging to thrive in a role that doesn't align with your strengths and interests. Participating in the BRI summer seminar or taking time to reflect during graduate school can help you better understand your aptitudes and aspirations.

While making too many mistakes can hinder daily progress, research is a field where "mistakes are allowed." It's common for hypotheses to be disproven, and even published papers often contain errors. Since my time as a student, I've observed how frequently textbooks are rewritten or updated, reflecting the ever-evolving nature of knowledge. The thrill of knowing something that no one else does is a feeling that's hard to experience in any other context--except, perhaps, in committing crimes. Furthermore, the work at BRI has the potential to make a real difference in people's lives. I'm deeply motivated by the desire to overcome intractable diseases, better understand disabilities, and leave a mark in the history of science. And who knows--you might be the one to achieve these breakthroughs.